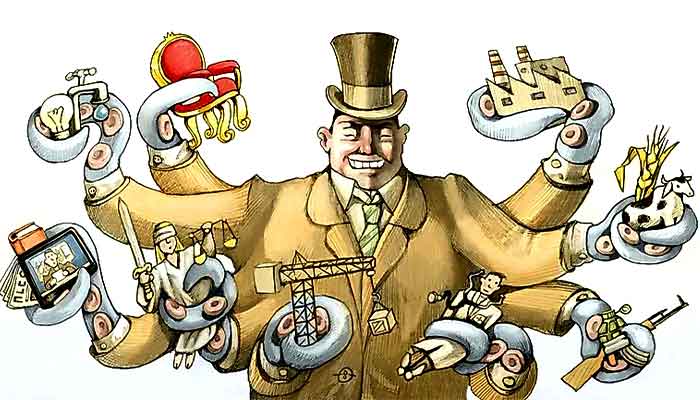

The current world situation is marked by an intensification of the crisis of capitalist globalisation. Its outcome will depend not only on objective economic developments but, crucially, on political conflicts, that is, battles over the control and use of society’s productive capacity. The most fundamental of these is the class struggle between capital and labour but they also include battles between, and within, the big capitalist powers.

We are, thus, entering a phase of global class struggles that will have a decisive influence on further development, a potential turning point in world history, with the following characteristics:

We are at the beginning of another global recession. This is exacerbated by the crisis of the world market and global value chains, the internal cyclical development of major imperialist powers, the impact and lasting consequences of the pandemic, the ecological crisis and the intensified open struggle for redivision of the world between the imperialist powers.

Unlike after the great financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent recession, a coordinated strategy by the leading imperialist powers in response to the global economic crisis is effectively excluded.

This not only aggravates the cyclical economic crisis in individual states, but also the inter-imperialist antagonisms, the tendencies towards “deglobalisation”, the fragmentation of the world market, the formation of blocs and the passing on of the costs of the crisis to the semi-colonial world. The war over Ukraine and the mutual sanctions that massively affect both sides have the effect of aggravating the crisis, just as the crisis increases mutual competition and the danger of war.

All this is fuelling the escalation of other fundamental problems of humanity, including climate change, species extinction and reaching the limits of capitalist agriculture. The pandemic that has claimed millions of lives, the threat of famine and the displacement of a billion climate refugees over the next 30 years are expressions of this development. The combination of economic crisis and the inter-imperialist struggle for the re-division of the world, will greatly intensify the crisis of the relationship between humanity and the environment.

The crisis is necessarily accompanied by attacks on the working class, the peasantry and the lower sections of the petty bourgeoisie. Today, inflation is at the centre of the attacks on the incomes and living conditions of the masses. However, with the development of the crisis could come a shift to deflation, with mass layoffs, closures, unemployment and underemployment, as is already the case for significant sections of the semi-colonies.

The great recession and global crisis of 2008-10 marked the beginning of the decline of the globalisation period. The imperialist bourgeoisies were able to counteract its effects through a policy of cheap money (Quantitative Easing). This limited the destruction of surplus capital in the imperialist centres and, above all, saved finance capital. However, the underlying causes of the crisis, falling profit rates and over-accumulation of capital, actually required such destruction and without it they were reproduced on a higher level in an upswing strongly supported by the expansion of fictitious capital.

Even before 2020, a new crisis was on the horizon. In the event, its development was overtaken by the Corona pandemic, which served to synchronise a huge downturn in global production – albeit in different circumstances from 2008. The structure of the world economy had shifted further, intensifying global competition between the imperialist powers. The scale of the pandemic, hitting all countries with full force in 2020, led to a collapse in production far greater than in 2008-10, from which the world economy has still not recovered.

Finally, the ability to counteract the crisis with the same means as after 2010 is very much reduced (for the semi-colonies long before 2020). The inner contradictions of the capitalist world order, economic, political and environmental, have intensified to such an extent that they now reinforce each other, creating the instability and conflicts with which humanity is now faced.

This sharpened phase of the crisis of globalisation necessarily also marks the beginning of a new chapter in the class struggle. It is one in which the working class and the oppressed worldwide are in a far more difficult position than after the 2008-10 crisis.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the bourgeoisie found itself on the defensive ideologically. The Arab revolutions and the pre-revolutionary escalation in Greece highlighted the potential for a turn in the class struggle and provided inspiration to the working class and masses worldwide for several years. Their advances took place despite an already deep crisis and illustrated the spontaneous revolutionary potential of the working class – but also its limits.

The defeats of those movements not only revealed the depth of the crisis of leadership of the proletariat, but also had a lasting global impact on the morale, combativity and consciousness of the working class. The shift in the balance of forces had reactionary consequences: the decomposition of traditional workers’ organisations and the rise of right-wing populism, including fascist and semi-fascist forces, which presented itself as a reactionary but anti-“elite” pseudo-radical solution. The political weakness of the workers’ movement is expressed precisely in the fact that, in almost all countries, the choice now appears to be one between the populist right wing and a “democratic” centre that includes the mass organisations of the proletariat.

The left, but also progressive mass movements like the women’s strikes or Black Lives Matter, and the militant wing of the working class itself, are very much influenced by petty-bourgeois and neo-reformist ideas (identity politics, individualism, left populism, transformation strategy). This global shift in the political and ideological balance of power is also expressed in a weakness of the subjectively revolutionary (centrist) left on the globe and in its adaptation to such ideologies.

Undoubtedly, the struggles of the last few years have created, and future struggles will again create, important opportunities for the re-formation of the working class – including large strike movements or insurrection-like revolts as in Sri Lanka. In some countries, as is currently the case with the Workers’ Party, PT, in Brazil, it may also happen that reformist parties, despite their treacherous policies, will once again attract the hopes and illusions of the working class. These will not last, but such movements and their radicalisation can only prepare the ground for a solution to the leadership crisis, they cannot themselves solve the problem.

This requires a targeted revolutionary intervention based on a clear, global programme whose central theme is the need to build organisations of workers’ control, not only to deal with immediate issues but to become the means of overthrowing capitalism and forming the basis of workers’ states. Parties based on such a programme will need to concretise and constantly update it in the form of national or section-specific action programmes. They will also need an understanding of how to apply principled tactics in party building, for example, regroupment, entrism or formation of a workers’ party, which can, nationally and internationally, advance the cause of a new, Fifth International.

- How do we consider the socio economics crisis in Sri Lanka in the world contest - October 18, 2023

- The Global Outlook - December 29, 2022

![Read more about the article ශ්රී ලංකාව පිළිබඳ UNDP වාර්තාව [2022-2023]: ජනගහණයෙන් 57% ක් බහුමාන අවදානම් හිරවීමක..](https://vivaranalk.com/wp-content/uploads/2023sSep4_2_F_naattami-300x172.jpg)