Dr Ajith Amarasinghe is a Consultant Paediatrician and a Clinical Allergist who holds an MBA in healthcare from the University of Manipal. He has held administrative positions in the public and private sectors.

On the eve of the Sinhala and Tamil New Year day of the 12th of April 2022, Sri Lanka pronounced that it is a bankrupt country by declaring that it cannot pay its debts. It is predicted that the shrinking economy of Sri Lanka will not bounce back to the level of 2018 for at least 3-5 years. The impact this state of bankruptcy would have on the health care of the people of Sri Lanka has not been discussed in depth. The ramifications of the effect of economic bankruptcy has on the health of Sri Lankans are multifaceted. To many, it would result in a shortage of medicine and healthcare equipment. Emergency measures are taken to obtain these, as donations from other countries or philanthropists. Although the loss of a human life due to lack of medications or services caused by an economic meltdown generates emotional and sensational stories, health care providers should look beyond these and take remedial steps to prevent a bigger health care catastrophe.

Sri Lanka spends about 3.4% of its GDP on healthcare, which amounted to Rs 423 billion in the year 2018. With a very low level of per capita health care spending of 161 USD, Sri Lanka has achieved very high levels of healthcare indices. In comparison, per capita health care spending in the USA is approximately USD 10,900, and in the UK USD 4,300. A country which has comparable health care indices such as Cuba spends six times that of Sri Lanka, being USD 1,321. In fact, Sri Lanka has become a success story in the eyes of international agencies, as a model where high health care indices and qualitatively higher levels of care have been achieved at a very low cost. Under these circumstances, further curtailment of per capita health care expenditure is near impossible. Although the Honorable Prime Minister emphasized in public that reducing health care expenditure would not be done at any cost, a shrinking economy would make this a necessity through compulsion. This article is an attempt to initiate a serious, in depth discussion about the impact the economic bankruptcy will have on the health care system in Sri Lanka, ways to minimize morbidity and mortality patterns in the country and to protect the nation’s overall health.

Private spending on health care

Although Sri Lanka boasts of having a “free” health care system, nearly half of its health care spending is through private sources. Private financing is done through out-of-pocket spending by patients, private insurance, insurance paid by enterprises, and contributions from non-profit organizations. Of all the private health spending, out-of-pocket expenditure by patients for medical care was 81% in the year 2018. In contrast, in many developed countries where a genuine free health system exists, direct government spending and widespread public health insurance schemes account for more than 90% of health care spending.

Although government spending on hospital (in patient care) expenditure is 74% and private spending is 24%, in non-hospital expenditure (outpatient care), private spending by patients is 77%. Overall, about 84% of the expenditure to supply medicines and other medical goods to outpatients was privately financed, mostly by household out-of-pocket spending. This indicates that when the economic meltdown affects individual income badly and the per capita income of Sri Lanka falls, outpatient care will be seriously affected. The exorbitant increase in prices of drugs due to the devaluation of the rupee would make it even more difficult to purchase essential medications. In recent months, certain drug prices have risen by 60%, forcing patients to reduce the quantity of medications they take or abandon taking medications at the expense of other essential commodities such as food, fuel, electricity, cooking gas, etc. This reduction in the buying power of medicines would mainly impact patients with non-communicable chronic diseases such as diabetes, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, renal diseases etc., in which lifelong treatment is essential.

To safeguard this economically marginalized segment of society and the “new poor” created by economic collapse, they will have to be helped by redirecting them to the government sector where drugs are provided free of charge. When this happens, the government’s expenditure on health care would naturally increase. The other option is to introduce a national health insurance scheme with government intervention, to cater to this segment, which is currently not serviced through government funding. Sri Lanka still has underdeveloped medical insurance schemes. Although company medical benefits, which provided 2% in 1999, increased to 9% in 2018, it is still a minute proportion of the total health care spending.

![2022June13[2]_private_health_care](https://vivaranalk.com/wp-content/uploads/2022June132_private_health_care-.png)

Public spending

In analyzing the sources of financing for health care expenditure, it could be observed that during the period of 1999 to 2018, the relative share of public financing in health care has increased from 40% to 58% and private financing has reduced from 60% to 42%. The central government’s share of public sector financing was 60%; provincial governments 32%; and local governments 2%. The Suraksha student insurance scheme and ETF contributed a minute 0.3% in the year 2018.

Government expenditure on health care is mainly financed from revenue generated through public taxation. The reduction of government taxation in the year 2019 had a strong impact on government revenue. In addition, the government obtains its income through foreign aid and loans. Due to the default of loans obtained, further harnessing of loans has become a near impossibility. All these would contribute to a drastic reduction in government income and, in turn, the ability of the government to spend on health care would be reduced. The practical solution would be to increase government taxation or even introduce a “social benefit tax” and use the revenue generated to maintain current levels of government financing of health, education and social services.

The contribution of donations through foreign sources to health care spending was less than 1% throughout the years. With the downfall of the economy, foreign donor agencies such as WHO, UNICEF, World Food Program, and international non-governmental organizations may come to our assistance, increasing the contribution of direct foreign donations to health care. Establishing a separate unit in the Ministry of Health to identify and harness the organizations that are willing to help Sri Lanka by harnessing their contributions and directing such donations to essential sections of health care is important. However, even with these measures, it would still be essential to cut down on government expenditure on health care. In the event of such a scenario, the healthcare managers should have a clear idea as to which expenditure should be curtailed.

Health care expenditure

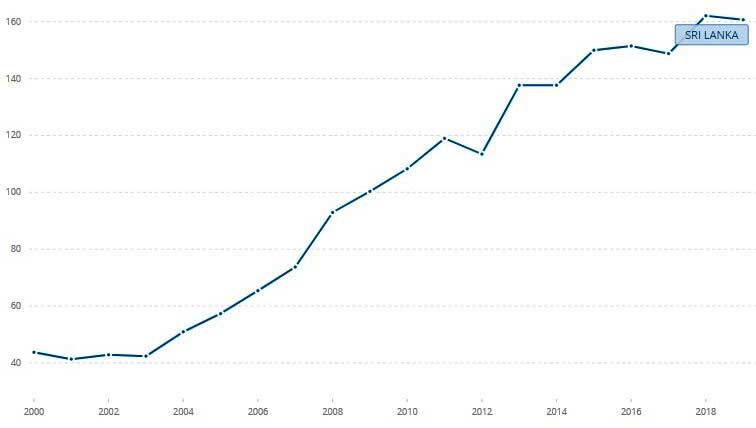

Current expenditure on health goods and services in Sri Lanka in 2018 was estimated at Rs. 423 billion. Overall, current health expenditure (CHE) nearly quadrupled in real terms between 1999 and 2018. Per capita Health expenditure of Sri Lanka increased from 44 US dollars in 2000 to 101 USD in 2010 to 161 US dollars in 2019 growing at an average annual rate of 7.44%.The ratio of CHE to GDP fluctuated between 2.6% and 3.7% during 1990–2019. This indicates that health care expenditure increased more or less proportionately to the increase in GDP. With the shrinking of GDP due to the economic downfall, it would necessarily mean that expenditure on health care would naturally be reduced. Going back to the 2009 level of spending patterns after proper cost-benefit analysis may become essential.

Health expenditure per capita (current US$) – (Sri Lanka)

Current, capital and total expenditure on health in real values (2018 prices) 1990–2018 (Real values expressed in terms of 2018 prices)

| Year | Current expenditure on health Rs. Million | Capital formation Rs. Million | Total health expenditure Rs. Million | Per capita current total health expenditure Rs | GDP per capita RS | Ratio of total health care expenditure to GDP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 140,899 | 22,258 | 163,157 | 8,916 | 247,190 | 3.6 |

| 2009 | 248,254 | 24,322 | 272,576 | 13,190 | 388,258 | 3.5 |

| 2018 | 423,219 | 58,070 | 481,289 | 22,485 | 671,158 | 3.4 |

Health care expenditure by activity

| In patient | Out patient | Pharmacy sales and medicine | Public health | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41% | 19% | 19% | 5% | 16% |

Current expenditure on institutions

| Year | Total spending in Rs million | Teaching hospitals and special hospitals (%) | Provincial, base, divisional hospitals (%) | Primary and MOOH (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 10, 598 | 48 | 44 | 9 |

| 2009 | 51,013 | 53 | 38 | 9 |

| 2019 (Estimated) | 203,168 | 59 | 35 | 6 |

The largest part of health spending is for curative inpatient care, which is mainly financed by public spending. Total spending on hospitals has quadrupled between 2009 and 2019 (estimated), and it has become more inclined towards large hospitals in this period. This is very likely to be due to spending on infrastructure development and purchasing expensive equipment for large hospitals. To reduce the cost of this segment, non-essential capital expenditure in inpatient care has to be curtailed. As the expenditure on health in an economically vulnerable period has to be done carefully, in the future, any government health care spending has to be done after careful cost-effective analysis by the Ministry of Health through a transparent scientific mechanism. A cost-effectiveness analysis is a method for assessing the gains in health relative to the costs of different health interventions. Even though it is not the only criterion to decide on the allocation of resources, relating the financial and healthcare implications of different interventions is important.

From 2009 to 2019, spending on healthcare institutions increased fourfold, with no significant improvement in communicable or non-communicable disease case fatality rates. During this period, mortality from cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic renal disease decreased from 22.3 to 17.5 percent. Therefore, if there is a need to reduce the costs, the government may have to take a difficult decision to roll back to the past to reduce the health care costs based on spending patterns of 2009.This may include curtailment of expensive drugs, instruments, equipment, and constructions .

To reduce the cost of purchasing medications, essential drug lists have to be made by respective professional colleges of specialties, based on scientific analysis of mortality and morbidity patterns. The purchase of quality generic drugs has to be done and a special unit has to be established in the MOH to coordinate the donated drugs and equipment monitoring. Distribution and maximum utilization of drugs has to be done through the currently underutilized IT based centralized method, to maximize utilization and minimize wastage. Producing drugs and equipment in Sri Lanka has to be done after a careful cost benefit analysis of the wisdom of producing each item in Sri Lanka.

Preventive health services

Of the total health expenditure, only 5% is spent on preventive care services, though the government’s slice of expenditure on preventive health is 98%. Expenditure on preventive health includes universal vaccination programs, family health worker network maintenance, health education, health promotion, and related public health services. Arguably, the current excellent health care indices of Sri Lanka were achieved through its spending on public (preventive) health. Therefore, the meager spending of 5% on public health should not be reduced at any cost. In fact, it may be essential to increase it to match the inflation, without which the public health services may collapse. Foreign donor agencies such as UNICEF and GAVI (Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization) should be requested to provide us with vaccinations free of charge for the expanded program of vaccinations (EPI), as it happened before we became a middle income country. Of the inpatient services, cost reduction should not be done at all in maternal and child health services.

Reduction in morbidity and mortality in communicable diseases, which were the main causes of illnesses in the past in Sri Lanka, was achieved through preventive health campaigns. Similarly, through public education campaigns, reductions in 1st and 2nd leading causes of hospitalization, namely traumatic injuries (most of which are domestic and occupational accidents) and non-communicable diseases, could be achieved.

Production of medicine

Encouraging local production of drugs is one proposal made to provide medicines at a lower cost. Although manufacturing medications would reduce the foreign exchange drain, the cost of producing certain drugs locally may be higher than importation. Therefore, encouraging local manufacturing with the intention of reducing prices has to be done after careful analysis on an individual basis.

Impact on nutrition

Souring food prices due to hyperinflation and food shortages caused by the shortsighted implementation of organic fertilizer policy has made food items unaffordable to the poor. This would result in acute and chronic protein energy malnutrition, vitamin and micronutrient deficiencies, especially in children and pregnant women, affecting future generations of the country. Health education and health promotion programs have to be conducted to make the public aware of cheap, nutritious food and a balanced diet. Common food programs for the poor, provision of micronutrient and vitamin supplementation programs to the vulnerable population, and the reintroduction of school mid-day meal programs through the existing public health and education structure may become essential. Utilization of existing official networks would ensure such programs are not politicized and ensure only the needy get the essential food items.

Conclusion

Although paying attention to the urgent supply of medication is an important aspect of saving human lives, it is critical that healthcare managers look beyond the medication shortage and initiate a serious scientific discussion about maintaining health services in Sri Lanka during the economic crisis. If this is not done soon, the population of Sri Lanka would face a major health care crisis which could not be salvaged by a late intervention.

Dr Ajith Amarasinghe- MBBS, DCH, MD (Sri Lanka), MRCP, MRCPCH (U.K), P.G Dip in Asthma & Allergy (CMC-Vellore), MBA-Health Care (Manipal) could be reached through amarasinghe_ajith@yahoo.com

References:

- Rannan-Eliya, Ravi P. Sri Lanka- “Good Practice” in Expanding Health Care Coverage – Institute for Health Policy Colombo- 2009

- Medical Statistics Unit- Annual health statistics 2019- Ministry of health Sri Lanka

- Ministry of health Sri Lanka-Annual health bulletin 2018- Ministry of health Sri Lanka

- Sarasi Nisansala Amarasinghe [et al.] – Sri Lanka health accounts: national health expenditure 1990- 2019 (IHP health expenditure series; No. 6) – Institute for Health Policy- Colombo- 2020

- World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory Data Repository- Mortality from CVD, cancer, diabetes or CRD between exact ages 30 and 70 male% -Sri Lanka- apps.who.int/ghodata.

- Department of Census and Statistics- Economic Statistics of Sri Lanka 2021- 5th bulletin- The Department of Census and Statistics 2021

- Department of Census and Statistics- The 2016 Sri Lanka Demographic and Health Survey-SLDHS- Department of Census and Statistics

- World Health Organization – Current health expenditure per capita (current US$) – Sri Lanka https://data.worldbank.org › SH.XPD.CHEX.PC.CD – 20th Jan 2022

- මේ නිදහස් සෞඛ්ය සේවයේ අවසානයද? - January 21, 2026

- දරුවන්ට ශාරීරික දඬුවම්දීම වැරදියි.. - October 13, 2025

- අධ්යාපන ප්රතිසංස්කරණයක්ද ? විෂයමාලා ප්රතිසංස්කරණක්ද ? අදහසක්වත් අධ්යාපන අමාත්යාංශයට නැහැ.. - August 11, 2025